Christopher Marlowe

| Christopher Marlowe | |

|---|---|

An anonymous portrait in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, often believed to show Christopher Marlowe. |

|

| Born | Baptized 26 February 1564 Canterbury, England |

| Died | 30 May 1593 (aged 29) Deptford, England |

| Occupation | Playwright, poet |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | circa 1586–93 |

| Literary movement | English renaissance theatre |

|

Influenced

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature | |

Christopher Marlowe[1] (baptised 26 February 1564–30 May 1593) was an English dramatist, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. As the foremost Elizabethan tragedian, next to William Shakespeare, he is known for his blank verse, his overreaching protagonists, and his mysterious death.

A warrant was issued for Marlowe's arrest on 18 May 1593. No reason for it was given, though it was thought to be connected to allegations of blasphemy—a manuscript believed to have been written by Marlowe was said to contain "vile heretical conceipts." He was brought before the Privy Council for questioning on 20 May, after which he had to report to them daily. Ten days later, he was stabbed to death by Ingram Frizer. Whether the stabbing was connected to his arrest has never been resolved.[2]

Contents |

Early life

Marlowe was born to a shoemaker in Canterbury named John Marlowe and his wife Catherine.[3] His date of birth is not known, but he was baptised on 26 February 1564, and likely to have been born a few days before. Thus he was just two months older than his great contemporary Shakespeare, who was baptised on 26 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Marlowe attended The King's School, Canterbury (where a house is now named after him) and Corpus Christi College, Cambridge on a scholarship and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1584.[4] In 1587 the university hesitated to award him his master's degree because of a rumour that he had converted to Roman Catholicism and intended to go to the English college at Rheims to prepare for the priesthood. However, his degree was awarded on schedule when the Privy Council intervened on his behalf, commending him for his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to the Queen.[5] The nature of Marlowe's service was not specified by the Council, but its letter to the Cambridge authorities has provoked much speculation, notably the theory that Marlowe was operating as a secret agent working for Sir Francis Walsingham's intelligence service.[6] No direct evidence supports this theory, although the Council's letter is evidence that Marlowe had served the government in some capacity.

Literary career

Dido, Queen of Carthage was Marlowe's first drama. Marlowe's first play performed on stage in London was Tamburlaine (1587) about the conqueror Timur, who rises from shepherd to warrior. It is among the first English plays in blank verse,[7] and, with Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy, generally is considered the beginning of the mature phase of the Elizabethan theatre. Tamburlaine was a success, and was followed with Tamburlaine Part II. The sequence of his plays is unknown; all deal with controversial themes.

The Jew of Malta, about a Maltese Jew's barbarous revenge against the city authorities, has a prologue delivered by a character representing Machiavelli.

Edward the Second is an English history play about the deposition of King Edward II by his barons and the Queen, who resent the undue influence the king's favourites have in court and state affairs.

The Massacre at Paris is a short and luridly written work, probably a reconstruction from memory of the original performance text,[8] portraying the events of the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572, which English Protestants invoked as the blackest example of Catholic treachery. It features the silent "English Agent", whom subsequent tradition has identified with Marlowe himself and his connections to the secret service.[9] Along with The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, The Massacre at Paris is considered his most dangerous play, as agitators in London seized on its theme to advocate the murders of refugees from the low countries and, indeed, it warns Elizabeth I of this possibility in its last scene.[10][11]

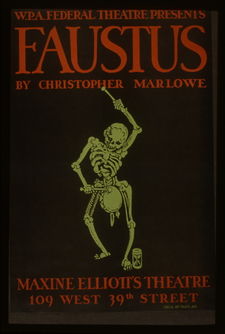

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, based on the German Faustbuch, was the first dramatised version of the Faust legend of a scholar's dealing with the devil. While versions of "The Devil's Pact" can be traced back to the 4th century, Marlowe deviates significantly by having his hero unable to "burn his books" or repent to a merciful God in order to have his contract annulled at the end of the play. Marlowe's protagonist is instead torn apart by demons and dragged off screaming to hell. Dr Faustus is a textual problem for scholars as it was highly edited (and possibly censored) and rewritten after Marlowe's death. Two versions of the play exist: the 1604 quarto, also known as the A text, and the 1616 quarto or B text. Many scholars believe that the A text is more representative of Marlowe's original because it contains irregular character names and idiosyncratic spelling: the hallmarks of a text that used the author's handwritten manuscript, or "foul papers", as a major source.

Marlowe's plays were enormously successful, thanks in part, no doubt, to the imposing stage presence of Edward Alleyn. He was unusually tall for the time, and the haughty roles of Tamburlaine, Faustus, and Barabas were probably written especially for him. Marlowe's plays were the foundation of the repertoire of Alleyn's company, the Admiral's Men, throughout the 1590s.

Marlowe also wrote Hero and Leander (published with a continuation by George Chapman in 1598), the popular lyric The Passionate Shepherd to His Love, and translations of Ovid's Amores and the first book of Lucan's Pharsalia.

The two parts of Tamburlaine were published in 1590; all Marlowe's other works were published posthumously. In 1599, his translation of Ovid was banned and copies publicly burned as part of Archbishop Whitgift's crackdown on offensive material.

The legend

As with other writers of the period, little is known about Marlowe. What little evidence there is can be found in legal records and other official documents. This has not stopped writers of both fiction and non-fiction from speculating about his activities and character. Marlowe has often been described as a spy, a brawler, a heretic and a homosexual, as well as a "magician", "duellist", "tobacco-user", "counterfeiter" and "rakehell". The evidence for most of these claims is limited. The bare facts of Marlowe's life have been embellished by many writers into colourful, and often fanciful, narratives of the Elizabethan underworld. However, J.B. Steane[12] remarked, "it seems absurd to dismiss all of these Elizabethan rumours and accusations as 'the Marlowe myth'"[13]

Spying

Marlowe is often alleged to have been a government spy. The author Charles Nicholl speculates this is so, and that Marlowe's recruitment took place when he was at Cambridge. Surviving college records from the period indicate Marlowe had a series of unusually lengthy absences from the university – much longer than permitted by university regulations – that began in the academic year 1584-1585. Surviving college buttery (dining room) accounts indicate he began spending lavishly on food and drink during the periods he was in attendance[14] – more than he could have afforded on his known scholarship income.

As noted above, in 1587 the Privy Council ordered Cambridge University to award Marlowe his MA, denying rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified "affaires" on "matters touching the benefit of his country". This is from a document dated 29 June 1587, from the Public Records Office – Acts of Privy Council.

It has sometimes been theorised that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to Arbella Stuart in 1589.[15] This possibility was first raised in a TLS letter by E. St John Brooks in 1937; in a letter to Notes and Queries, John Baker has added that only Marlowe could be Arbella's tutor due to the absence of any other known "Morley" from the period with an MA and not otherwise occupied.[16] If Marlowe was Arbella's tutor, (and some biographers think that the "Morley" in question may have been a brother of the musician Thomas Morley[17]) it might indicate that he was a spy, since Arbella, niece of Mary, Queen of Scots, and cousin of James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, was at the time a strong candidate for the succession to Elizabeth's throne.[18]

In 1592 Marlowe was arrested in the Dutch town of Flushing for attempting to counterfeit coins and use the proceeds to assist seditious Catholics. He was sent to be dealt with by the Lord Treasurer (Burghley) but no charge or imprisonment resulted.[19] This arrest may have disrupted another of Marlowe's spying missions: by giving the resulting coinage to the Catholic cause he was to infiltrate the followers of the active Catholic plotter William Stanley and report back to Burghley.[20]

Arrest and death

In early May 1593 several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel,"[21] written in blank verse, contained allusions to several of Marlowe's plays and was signed, "Tamburlaine". On 11 May the Privy Council ordered the arrest of those responsible for the libels. The next day, Marlowe's colleague Thomas Kyd was arrested. Kyd's lodgings were searched and a fragment of a heretical tract was found. Kyd asserted, possibly under torture, that it had belonged to Marlowe. Two years earlier they had both been working for an aristocratic patron, probably Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange,[22] and Kyd suggested that at this time, when they were sharing a workroom, the document had found its way among his papers. Marlowe's arrest was ordered on 18 May. Marlowe was not in London, but was staying with Thomas Walsingham, the cousin of the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth's principal secretary in the 1580s and a man deeply involved in state espionage.[23] However, he duly appeared before the Privy Council on 20 May and was instructed to "give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary". On 30 May, Marlowe was killed.

Various versions of Marlowe's death were current at the time. Francis Meres says Marlowe was "stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love" as punishment for his "epicurism and atheism."[24] In 1917, in the Dictionary of National Biography, Sir Sidney Lee wrote that Marlowe was killed in a drunken fight, and this is still often stated as fact today.

The facts only came to light in 1925 when the scholar Leslie Hotson discovered the coroner's report on Marlowe's death in the Public Record Office.[25] Marlowe had spent all day in a house in Deptford, owned by the widow Eleanor Bull. With him were three men: Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley.[26] All three had been employed by the Walsinghams. Skeres and Poley had helped snare the conspirators in the Babington plot and Frizer was a servant of Thomas Walsingham. Witnesses testified that Frizer and Marlowe had earlier argued over the bill for their drink (now famously known as the 'Reckoning') exchanging "divers malicious words". Later, while Frizer was sitting at a table between the other two and Marlowe was lying behind him on a couch, Marlowe snatched Frizer's dagger and began attacking him. In the ensuing struggle, according to the coroner's report, Marlowe was accidentally stabbed above the right eye, killing him instantly. The jury concluded that Frizer acted in self-defence, and within a month he was pardoned. Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford, on 1 June 1593.

Marlowe's death is alleged by some to be an assassination for the following reasons:

- The three men who were in the room with him when he died were all connected both to the state secret service and to the London underworld.[27] Frizer and Skeres also had a long record as loan sharks and con-men, as shown by court records. Bull's house also had "links to the government's spy network".[28]

- Their story that they were on a day's pleasure outing to Deptford is alleged to be implausible. In fact, they spent the whole day closeted together, deep in discussion. Also, Robert Poley was carrying confidential despatches to the Queen, who was at her residence Nonsuch Palace in Surrey, but instead of delivering them, he spent the day with Marlowe and the other two.[29]

- It seems too much of a coincidence that Marlowe's death occurred only a few days after his arrest for heresy.

- The manner of Marlowe's arrest is alleged to suggest causes more tangled than a simple charge of heresy would generally indicate. He was released in spite of prima facie evidence, and even though the charges implicitly connected Sir Walter Raleigh and the Earl of Northumberland with the heresy. Thus, some contend it to be probable that the investigation was meant primarily as a warning to the politicians in the "School of Night", or that it was connected with a power struggle within the Privy Council itself.[30]

- The various incidents that hint at a relationship with the Privy Council (see above), and by the fact that his patron was Thomas Walsingham, Sir Francis's second cousin, who was actively involved in intelligence work.

For these reasons and others, Charles Nicholl (in his book 'The Reckoning' on Marlowe's death) argues there was more to Marlowe's death than emerged at the inquest. There are different theories of some degree of probability. Since there are only written documents on which to base any conclusions, and since it is probable that the most crucial information about his death was never committed to writing at all, it is unlikely that the full circumstances of Marlowe's death will ever be known.

Atheism

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist which, at that time, held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God.[31] Modern historians, however, consider that his professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than an elaborate and sustained pretence adopted to further his work as a government spy.[32] Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in Flushing, an informer called Richard Baines. The governor of Flushing had reported that both men had accused one "of malice one to another" of instigating the counterfeiting, and of intention to go over to Catholicism; such an action was considered atheistic by the Protestants, who constituted the dominant religious faction in England at that time. Following Marlowe's arrest on a charge of atheism in 1593, Baines submitted to the authorities a "note containing the opinion of one Christopher Marly concerning his damnable judgment of religion, and scorn of God's word."[33] Baines attributes to Marlowe a total of eighteen items which "scoff at the pretensions of the Old and New Testament"[13] such as, "Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest [unchaste]", "the woman of Samaria and her sister were whores and that Christ knew them dishonestly", and, "St John the Evangelist was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom" (cf. John 13:23-25), and, "that he used him as the sinners of Sodom". He also claims that Marlowe had Catholic sympathies. Other passages are merely sceptical in tone: "he persuades men to atheism, willing them not to be afraid of bugbears and hobgoblins". The final paragraph of Baines' document reads:

These thinges, with many other shall by good & honest witnes be aproved to be his opinions and Comon Speeches, and that this Marlow doth not only hould them himself, but almost into every Company he Cometh he perswades men to Atheism willing them not to be afeard of bugbeares and hobgoblins, and vtterly scorning both god and his ministers as I Richard Baines will Justify & approue both by mine oth and the testimony of many honest men, and almost al men with whome he hath Conversed any time will testify the same, and as I think all men in Cristianity ought to indevor that the mouth of so dangerous a member may be stopped, he saith likewise that he hath quoted a number of Contrarieties oute of the Scripture which he hath giuen to some great men who in Convenient time shalbe named. When these thinges shalbe Called in question the witnes shalbe produced.[34]

Similar statements were made by Thomas Kyd after his imprisonment and possible torture (see above);[35][36] both Kyd and Baines connect Marlowe with the mathematician Thomas Harriot and Walter Raleigh's circle. Another document claims that Marlowe had read an "atheist lecture" before Raleigh; a man called Richard Chomley was charged with atheism and treason shortly after Marlowe's death, and noted in his testimony that "one Marlowe is able to show more sound reasons from atheism than any divine in England is able to give to prove divinity and that Marlowe told him that he hath read the atheist lecture to Sir Walter Raleigh and others".[13]

Some critics believe that Marlowe sought to disseminate these views in his work and that he identified with his rebellious and iconoclastic protagonists.[37] However, plays had to be approved by the Master of the Revels before they could be performed, and the censorship of publications was under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Presumably these authorities did not consider any of Marlowe's works to be unacceptable (apart from the Amores).

Sexuality

Like his contemporary William Shakespeare, Marlowe is sometimes described today as homosexual. Some believe that the question of whether an Elizabethan was "gay" or "homosexual" in a modern sense is anachronistic; for the Elizabethans, what is often today termed homosexual or bisexual was more likely to be recognised as simply a sexual act, rather than an exclusive sexual orientation and identity.[38]

Some scholars argue that the evidence is inconclusive and that the reports of Marlowe's homosexuality may simply be exaggerated rumours produced after his death. Richard Baines reported Marlowe as saying: "All they that love not Tobacco and Boys are fools". David Bevington and Eric Rasmussen describe Baines's evidence as "unreliable testimony" and make the comment: "These and other testimonials need to be discounted for their exaggeration and for their having been produced under legal circumstances we would regard as a witch-hunt".[39] One critic, J.B. Steanes, remarked that he considers there to be "no evidence for Marlowe's homosexuality at all."[13]

Other scholars,[40] however, point to homosexual themes in Marlowe's writing: in Hero and Leander, Marlowe writes of the male youth Leander, "in his looks were all that men desire"[41] and that when the youth swims to visit Hero at Sestos, the sea god Neptune becomes sexually excited, "imagining that Ganymede, displeas'd... the lusty god embrac'd him, call'd him love... and steal a kiss... upon his breast, his thighs, and every limb ... [a]nd talk of love",[42] while the boy naive and unaware of Greek love practices said that, "You are deceiv'd, I am no woman, I... Thereat smil'd Neptune."[43]

Reputation among contemporary writers

Whatever the particular focus of modern critics, biographers and novelists, for his contemporaries in the literary world, Marlowe was above all an admired and influential artist. Within weeks of his death, George Peele remembered him as "Marley, the Muses' darling"; Michael Drayton noted that he "Had in him those brave translunary things/That the first poets had", and Ben Jonson wrote of "Marlowe's mighty line". Thomas Nashe wrote warmly of his friend, "poor deceased Kit Marlowe". So too did the publisher Edward Blount, in the dedication of Hero and Leander to Sir Thomas Walsingham.

Among the few contemporary dramatists to say anything negative about Marlowe was the anonymous author of the Cambridge University play The Return From Parnassus (1598) who wrote, "Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell,/Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell."

The most famous tribute to Marlowe was paid by Shakespeare in As You Like It, where he not only quotes a line from Hero and Leander (Dead Shepherd, now I find thy saw of might, "Who ever loved that loved not at first sight?") but also gives to the clown Touchstone the words "When a man's verses cannot be understood, nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room." This appears to be a reference to Marlowe's murder which involved a fight over the "reckoning" – the bill.

Shakespeare was heavily influenced by Marlowe in his early work, as can be seen in the re-using of Marlovian themes in Antony and Cleopatra, The Merchant of Venice, Richard II, and Macbeth (Dido, Jew of Malta, Edward II and Dr Faustus respectively). In Hamlet, after meeting with the travelling actors, Hamlet requests the Player perform a speech about the Trojan War, which at 2.2.429-32 has an echo of Marlowe's Dido, Queen of Carthage. Indeed, in Love's Labour's Lost, echoing Marlowe's The Massacre at Paris, Shakespeare brings on a character called Marcade (French for Mercury – a god who, in Hero and Leander, is responsible for advancing scholars from poor backgrounds and identified by Marlowe with his own humble origin[44] ) who arrives to interrupt the merriment with news of the King's death. This is a fitting tribute for one who delighted in destruction in his plays.

As Shakespeare

Given the murky inconsistencies concerning the account of Marlowe's death, a theory has arisen centred on the notion that Marlowe may have faked his death and then continued to write under the assumed name of William Shakespeare. Authors who have propounded this theory include:

- Wilbur Gleason Zeigler It Was Marlowe (1895)

- Calvin Hoffman, The Man Who Was Shakespeare, Mitre Press (1955)[45]

- Calvin Hoffman, The Murder of the Man Who Was Shakespeare, Grosset & Dunlap (1960)

- Daryl Pinksen, Marlowe's Ghost (2008)

- Samuel Blumenfeld's The Marlowe-Shakespeare Connection: A New Study of the Authorship Question

- Louis Ule, Christopher Marlowe (1564–1607): A Biography

- A D Wraight, The Story that the Sonnets Tell (1994)

- Roderick L Eagle, The Mystery of Marlowe's Death, N&Q (1952)

- William Honey, The Shakespeare Epitaph Deciphered, Mitre Press (1969)

- Rodney Bolt, History Play, Harper Collins (2004)

Works

The dates of composition are approximate.

Plays

- Dido, Queen of Carthage (c.1586) (possibly co-written with Thomas Nashe)

- Tamburlaine, part 1 (c.1587)

- Tamburlaine, part 2 (c.1587-1588)

- The Jew of Malta (c.1589)

- Doctor Faustus (c.1589, or, c.1593)

- Edward II (c.1592)

- The Massacre at Paris (c.1593)

The play Lust's Dominion was attributed to Marlowe upon its initial publication in 1657, though scholars and critics have almost unanimously rejected the attribution.

Poetry

- Translation of Book One of Lucan's Pharsalia (date unknown)

- Translation of Ovid's Elegies (c. 1580s?)

- The Passionate Shepherd to His Love (pre-1593; because it is constantly referred to in his own plays we can presume an early date of mid-1580s)

- Hero and Leander (c. 1593, unfinished; completed by George Chapman, 1598)

In fiction

- The Conscience of the King is a historical novel by Martin Stephen which features Marlowe, having faked his death in 1593, in action in 1612 in London.

- Upstart Crows is a play written by Mike Punter that centres around the life of Marlowe, Edward Alleyn, Jack Alleyn and other characters.

- A play called The Reckoning of Kit & Little Boots, written by Nat Cassidy, examines the life and death of Marlowe, juxtaposed with the life of the Roman emperor Caligula, via the conceit that at the time of his death Marlowe is working on a play about Caligula.

- Marlowe was the title character of Marlowe, a 1981 stage musical that had a brief Broadway run.

- Marlowe is the title character in Francis Hamit's play Marlowe: An Elizabethan Tragedy, produced, June 1988 by The Shakespeare Society of America. West Hollywood, California. It detailed his entire career as a spy for the early English Secret Service. Play script to be reissued in 2010.

- Marlowe is a central character in Lisa Goldstein's fantasy novel Strange Devices of the Sun and Moon

- Connie Willis's Winter's tale features Marlowe as a major character.

- Louise Welsh's Tamburlaine Must Die is a novel based on a fictitious theory about the last two weeks of Marlowe's life.

- Leslie Silbert's The Intelligencer, a novel, intertwines Marlowe as a possible spy in his time and events in the present, Washington Square Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7434-3292-4

- Anthony Burgess's novel A Dead Man in Deptford is an account of Marlowe and his death; according to Burgess, it is fictionalised but does not depart from any known historical facts.

- Marlowe is the central character in One Dagger for Two by Philip Lindsay, which includes some speculation about his death.

- Marlowe is the central character in The Christopher Marlowe Mysteries written by Ged Parsons for BBC Radio 4 (1993) and subsequently re-broadcast on BBC Radio 7. This was a series of comedy adventures revolving around Marlowe's work as a spy, starring Dominic Jephcott as Marlowe, Paul Brook as Sir Francis Walsingham and Bill Wallis as Ratsbane, his servant/accomplice.

- On August 17, 2010 BBC Radio 4 broadcast Unauthorized History: The Killing by Michael Butt as part of their Afternoon Play series. While Marlowe himself does not appear, the play deals with an investigation into his unsolved murder in May 1593. The cast included Paul Rhys as the Narrator, Christine Kavanagh as Mrs. Bull, Blake Ritson as Thomas Walsingham, Harry Lloyd as Thomas Kyd, Tim McMullan as Lord Cecil, Burn Gorman as Robert Poley and Tony Bell as Ingram Frizer; the production was directed by Sasha Yevtushenko.

- Christian Camargo played the role of Kit Marlowe in the 2001 production of David Grimm's Kit Marlowe at the New York Public Theater. The production was a dark portrayal of Marlowe's life as a spy, playwright and lover.

- Marlowe is the central character in a play by Peter Whelan called The School of Night that deals with his playwriting career after his faked death at Deptford.

- The Agony of Marlowe, a play written by Mark Cubillos, parallels the life of Christopher Marlowe and his most famous character, Dr. Faustus.

- Marlowe, a play written by Croatian writer Vladimir Stojsavljević, directed in Ljubljana, Slovenia by Dragan Živadinov in 2009.

Notes

- ↑ "Christopher Marlowe was baptised as 'Marlow,' but he spelled his name 'Marley' in his one known surviving signature." David Kathman. "The Spelling and Pronunciation of Shakespeare's Name: Pronunciation."

- ↑ Nicholl, Charles (2006). "By my onely meanes sett downe: The Texts of Marlow's Atheism", in Kozuka, Takashi and Mulryne, J.R. Shakespeare, Marlowe, Jonson: new directions in biography. Ashgate Publishing, p. 153.

- ↑ This is commemorated by the name of the town's main theatre, the Marlowe Theatre, and by the town museums. However, St. George's was gutted by fire in the Baedeker raids and was demolished in the post-war period - only the tower is left, at the south end of Canterbury's High Street http://www.digiserve.com/peter/cant-sgm1.htm

- ↑ Marlowe, Christopher in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ For a full transcript, see Peter Farey's Marlowe page

- ↑ He died in a deadly brawl.Hutchinson, Robert (2006). Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the secret war that saved England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 111. ISBN 0 297 84613 2.

- ↑ http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/16century/topic_1/welcome.htm See especially the middle section in which the author shows how another Cambridge graduate, Thomas Preston makes his title character express his love in a popular play written around 1560 and compares that "clumsy" lines with Doctor Faustus addressing Helen of Troy.

- ↑ Deats, Sarah Munson (2004). "'Dido Queen of Carthage' and 'The Massacre at Paris'". In Cheney, Patrick. The Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-521-82034-0.

- ↑ Wilson, Richard (2004). "Tragedy, Patronage and Power". in Cheney, Patrick, 2007, p. 207

- ↑ Nicholl, Charles (1992). "Libels and Heresies". The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 41. ISBN 0224031007.

- ↑ Hoenselaars, A. J. (1992). "Englishmen abroad 1558—1603". Images of Englishmen and Foreigners in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0838634311.

- ↑ J. B. Steane was a Scholar of Jesus College, Cambridge, where he read English. He is the author of Marlowe: A Critical Study and he edited and wrote an introduction to the Penguin English Library edition of Christopher Marlowe: The Complete Plays.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Steane, J.B. (1969). Introduction to Christopher Marlowe: The Complete Plays. Aylesbury, UK: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-043-037-7.

- ↑ Nicholl, Charles (1992). "12". The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224031007.

- ↑ He was described by Arbella's guardian, the Countess of Shrewsbury, as having hoped for an annuity of some £40 from Arbella, his being "so much damnified (i.e. having lost this much) by leaving the University.": BL Lansdowne MS 71,f.3.and Charles Nicholl, The Reckoning (1992), pp. 340-2.

- ↑ John Baker, letter to Notes and Queries 44.3 (1997), pp. 367-8

- ↑ Constance Kuriyama, Christopher Marlowe: A Renaissance Life (2002), p. 89. Also in Handover's biography of Arbella, and Nicholl, The Reckoning, p. 342.

- ↑ Elizabeth I and James VI and I, History in Focus.

- ↑ For a full transcript, see Peter Farey's Marlowe page

- ↑ Nicholl (1992: 246-248)

- ↑ A Libell, fixte vpon the French Church Wall, in London

- ↑ Mulryne, J. H. "Thomas Kyd." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ↑ Haynes, Alan. The Elizabethan Secret Service. London: Sutton, 2005.

- ↑ Palladis Tamia. London, 1598: 286v-287r.

- ↑ The Coroner's Inquisition (Translation)

- ↑ E. de Kalb, Robert Poley's Movements as a Messenger of the Court, 1588 to 1601 Review of English Studies, Vol. 9, No. 33

- ↑ Seaton, Ethel. "Marlowe, Robert Poley, and the Tippings." Review of English Studies 5 (1929): 273.

- ↑ Greenblatt, Stephen Will in the World. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004: 268.

- ↑ Nicholl (1992: 32)

- ↑ Gray, Austin. "Some Observations on Christopher Marlowe, Government Agent." PMLA 43 (1928): 692-4.

- ↑ Stanley, Thomas (1687). The history of philosophy 1655–61. quoted in Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ Riggs, David (2004). Cheney, Patrick. ed. The Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0521527341.

- ↑ The 'Baines Note' (1)

- ↑ "The 'Baines Note'". http://www2.prestel.co.uk/rey/baines1.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Kyd's Accusations

- ↑ Kyd's letter to Sir John Puckering

- ↑ Waith, Eugene. The Herculean Hero in Marlowe, Chapman, Shakespeare, and Dryden. London: Chatto and Windus, 1962. The idea is commonplace, though by no means universally accepted.

- ↑ Smith, Bruce R. (March 1995). Homosexual desire in Shakespeare's England. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-226-76366-8.

- ↑ Doctor Faustus and Other Plays, pp. viii - ix

- ↑ White, Paul Whitfield, ed. (1998). Marlowe, History and Sexuality: New Critical Essays on Christopher Marlowe. New York: AMS Press.

- ↑ Hero and Leander, 88 (see Project Gutenberg).

- ↑ Hero and Leander, 157-192.

- ↑ Hero and Leander, 192-193.

- ↑ Huntington, John (2001). Ambition, Rank, and Poetry in 1590s England. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-252-02628-4.

- ↑ frontline: much ado about something: readings: from the murder of the man who was shakespeare PBS

Additional reading

- Brooke, C.F. Tucker. The Life of Marlowe and "The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage." London: Methuen, 1930. (pp. 107, 114, 99, 98)

- Bevington, David and Eric Rasmussen, Doctor Faustus and Other Plays, OUP, 1998; ISBN 0-19-283445-2

- Burgess, Anthony, A Dead Man in Deptford, Carroll & Graf, 2003. (novel about Marlowe based on the version of events in The Reckoning) ISBN 0-7867-1152-3

- Marlow, Christopher. Complete Works. Vol. 3: Edward II. Ed. R. Rowland. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994. (pp. xxii-xxiii)

- Downie, J. A. and J. T. Parnell, eds., Constructing Christopher Marlowe, Cambridge 2000. ISBN 0-521-57255-X

- Honan, Park. Christopher Marlowe Poet and Spy Oxford University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-19-818695-9

- Kuriyama, Constance. Christopher Marlowe: A Renaissance Life. Cornell University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8014-3978-7

- Nicholl, Charles. The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe, Vintage, 2002 (revised edition) ISBN 0-09-943747-3

- Parker, John. The Aesthetics of Antichrist: From Christian Drama to Christopher Marlowe. Cornell University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8014-4519-4

- Riggs, David. "The World of Christopher Marlowe", Henry Holt and Co., 2005 ISBN 0-8050-8036-8

- Shepard, Alan. "Marlowe's Soldiers: Rhetorics of Masculinity in the Age of the Armada", Ashgate, 2002. ISBN 0-7546-0229-X

- Trow, M. J. Who Killed Kit Marlowe?, Sutton, 2002; ISBN 0-7509-2963-4

- Ule, Louis. Christopher Marlowe (1564–1607): A Biography, Carlton Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8062-5028-3

- Welsh, Louise. "Tamburlaine Must Die", novella based on the build up to Marlowe's death.

- Wraight, A.D. and Virginia F. Stern, In Search of Christopher Marlowe: A Pictorial Biography, Macdonald, London 1965

External links

- The Marlowe Society

- The works of Marlowe at Perseus Project

- Works by Christopher Marlowe in e-book

- Marlowe Collection at Bartleby.com

|

|||||||||||